A better vaccine against Ebola?

Weizmann study may show the way

Briefs

A vaccine that protects against Ebola—one of the world’s deadliest viral diseases—was recently approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the first time any immunization against Ebola has passed this hurdle. But while this vaccine, first developed by Merck in 2003, has already helped to control deadly outbreaks of the virus, no one knows exactly how Ebola vaccines activate the body’s immune system to fight the virus, or whether such vaccines provide long-term protection.

Now, research by Dr. Ron Diskin of the Weizmann Institute, conducted together with colleagues at the University of Cologne in Germany, has decoded just how this leading Ebola vaccine stimulates the immune system, and has also suggested how, in future versions of the vaccine, the generation of Ebola-fighting antibodies might be improved. What’s more, the scientists showed that subjects who receive a small dose of the vaccine generate similar profile of antibodies to subjects who had received a higher dose. This may help future vaccines be administered to more people, at lower cost.

The findings, which have important implications for rolling back the current Ebola epidemic, were reported in Nature Medicine on October.

In the study, Dr. Florian Klein, an immunologist from the University of Cologne, examined blood samples from six people who had previously received an Ebola vaccine, and isolated a number of antibodies that bound to Ebola virus proteins. Dr. Diskin then selected two of these antibodies, which they thought most likely to be involved in long-term immune response, for further study.

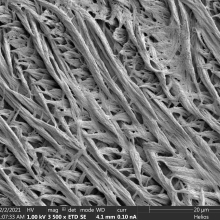

Using a recently acquired, high-power electron microscope, Dr. Diskin was able to clarify the three-dimensional structure of how antibodies bound to the Ebola virus. Using this data, the Diskin team made an important discovery: that the two antibodies they had selected bound to Ebola proteins using different binding mechanisms than seen in other antibodies. Moreover, when the scientists created a map of these antibodies’ unique binding sites, they noted that the antibodies’ binding locations matched what is seen in Ebola survivors—individuals who contracted Ebola and recovered.

This discovery—validated by lab studies in Cologne in which the Diskin team’s antibodies potently targeted and destroyed a live Ebola virus—suggests that the unique binding mechanism seen in the two antibodies could contribute to the efficacy of a future version of the Ebola vaccine.

Meanwhile, the scientists also found that subjects who received a smaller dose of the vaccine generated a similar profile of Ebola-fighting antibodies compared with subjects who had received a higher dose. This efficiency might decrease the cost of producing the vaccine, something that would help Africa’s financially strapped health services deliver more doses of the vaccine, to more people, and save lives.

Dr. Ron Diskin’s research is supported by the Moross Integrated Cancer Center; the Dr. Barry Sherman Institute for Medicinal Chemistry; the Jeanne and Joseph Nissim Center for Life Sciences Research; and the estate of Emile Mimran.

Dr. Ron Diskin