"Eye Contact - Seeing “what’s there”"Open week days: Sunday to Wednesdays, 09:00 – 16:00 Closed on Thursdays and weekends1

Lia Addadi, Alon Olearchik, Dan Oron, Valeriy Ayzenberg, Eliahu Eric Bucobza, Hadar Burstein, Erez Biton, Ronen Basri, Gidi Gov, Yehonatan Geffen, Steve Weiner, Eduardo Zatara, Shai Zilberman, Shlomi Hatuka, Orit Ishay, Idit Levavi Gabai, Suren Manvelyan, Etty Spindel, Benjamin Palmer, Yehuda Poliker, Gilit Fisher, Tal Peleg, Dorit Feldman

In the rivalry between the image and the written word, or between vision, hearing and the other senses, the victor is clear. We say: “I’ll believe it when I see it.” Eyewitnesses are the more reliable than those who testify based on “hearsay” (and testimony based, for example on smell, taste or touch is all but non-existent). The danger of the subjugation the other senses to sight in human experience caused Plato to state that artists, who create images, were not to be part of the ideal state. Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872) cautioned against the preference for the image over the thing itself, the copy over the original, the display over the actual, the mirror image over the solid presence.

Despite all these warnings, our sense of vision has never been more central, even reaching monopolistic levels when it comes to our interaction with the world. Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) described how the “visual society” is based on symbols and images we have created, and these have replaced reality with simulation of reality, or “hyperreality.”

The domination of the image, the “trustworthy” scene, diminishes and atrophies our imagination, our “third eye;” and in doing so, it weakens our ability to see other facets or more nuanced aspects of the “thing” we see before our eyes. It seems that the sharper the physical vision, the more it flattens and smoothes the image of reality that we process for ourselves when we perceive with our eyes. Seeing and speaking are two different kinds of acts in our minds, and we symbolize them in different ways, so when we say the “book was better than the movie,” it is because we inherently experience them differently.

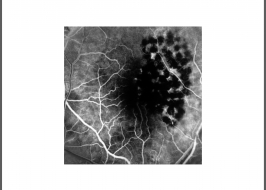

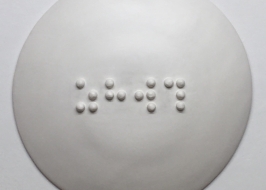

This suggests that certain failures of vision – even blindness – can slow sensory overload and enable perception, or the formation of a clearer picture of reality. Stevie Wonder put it best: “Just because a man lacks the use of his eyes doesn't mean he lacks vision.”

The technologies that were originally designed to broaden our visual input are likely to enslave our viewpoint and limit it. With the “vision machines” as Paul Virilio called them, “the industrial proliferation of visual and audiovisual prostheses and unrestrained use of instantaneous-transmission equipment from earliest childhood onwards, we now routinely see the encoding of increasingly elaborate mental images together with a steady decline in retention rates and recall.”

This exhibit featuring the work of scientists and artists, proposes a view that encourages us to examine the mechanisms by which we see the world, and the ways in which we decipher and decode the input of our senses.

Curator: Yivsam Azgad

The Edna and K.B. Weissman Building of Physical Sciences and the Nehemiah and Naomi Cohen building, Faculty of Physics

Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot

Scientists meet Artists

(*Speeches in Hebrew)