Tackling tuberculosis

Study finds new methods for identifying risk for active TB

Briefs

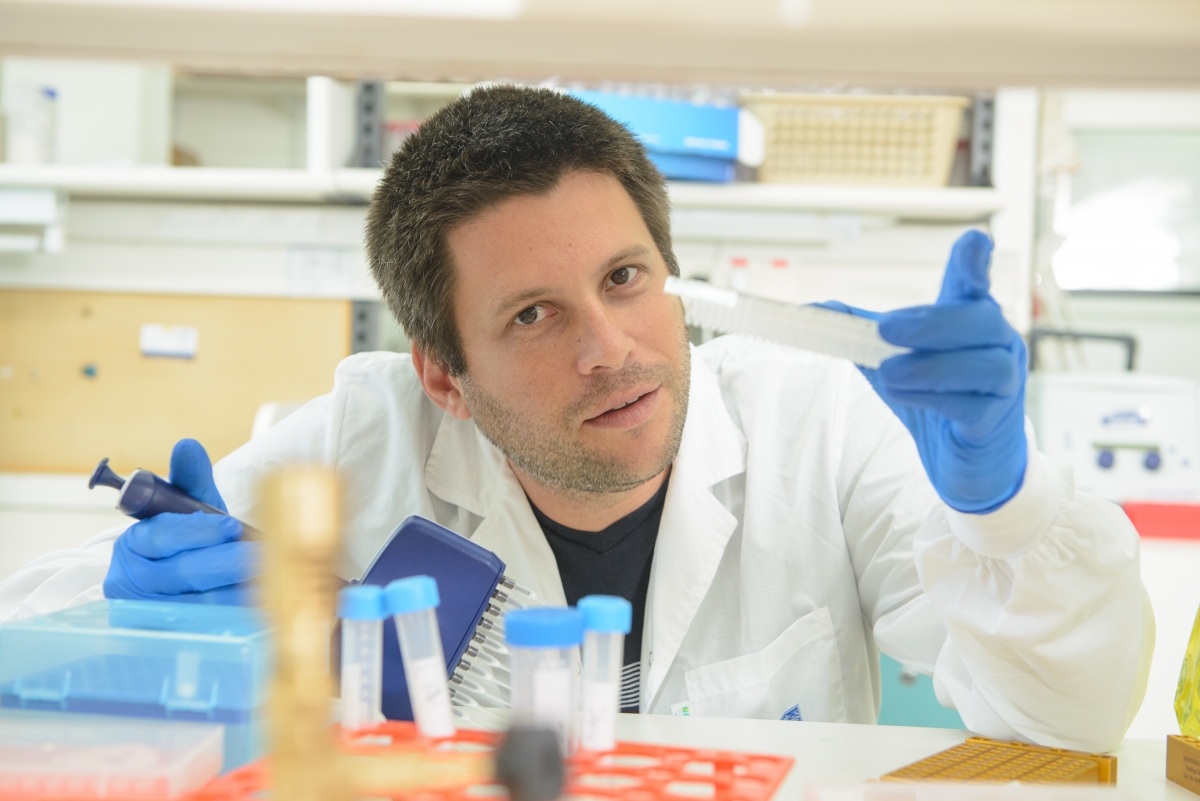

Weizmann Institute scientists led by Dr. Roi Avraham have developed a new way to identifies latent carriers of tuberculosis (TB) who are at highest risk of developing an active disease. The research could pave the way towards treating TB in its latent form and aid in overall prevention. The study was published in Nature Communications.

TB is caused by bacteria called Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The bacteria usually attack the lungs, but they can also damage other parts of the body. The World Health Organization estimates that 1 in 3 people living today has latent TB infection—that is, they are infected but have no symptoms because the bacteria are dormant. Between five and 10 percent of people with a latent infections will progress to active and infectious TB disease, and some two million people die of the disease every year. However, no test exists that can accurately predict who will develop active TB. Moreover, all TB patients must take a course of antibiotics for up to nine months, and antibiotic resistance is a major concern.

Dr. Roi Avraham

The study focused on the dynamic interactions that occur between host immune cells and pathogens—in this case, between human immune cells in the blood and Salmonella or TB bacteria. When an immune cell and bacterium meet, there can be several outcomes. The immune system can kill the bacteria; the bacteria can overcome the immune defenses; or, in the case of diseases like tuberculosis, the bacterium can lie dormant for years, sometimes causing disease at a later stage and sometimes remaining in hibernation for good. Dr. Avraham’s lab hypothesized that the junction at which one of those paths is taken happens early on—some 24-48 hours after infection.

By determining the genetic activity of thousands of cells in response to infection, the scientists revealed patterns not seen in standard blood lab tests—and found that there were marked differences in immune-cell activation between latent cells that progressed to active disease and those who remained healthy. At the heart of the study is an algorithm developed in the Avraham lab that can identify different immune cell types and genetic response patterns to infections from standard single-cell RNA sequence data; the algorithm flags those response patterns associated with an elevated risk for different infectious diseases.

“If those who are at risk of active disease could be identified when the bacterial load is smaller, their chances of recovery will be better,” says Dr. Avraham, from the Department of Biological Regulation. “And the medical systems in countries where TB is endemic might have a better way to keep down the suffering and incidence of sickness while reducing the cost of treatment.”

Dr. Roi Avraham is supported by the Merle S. Cahn Foundation, the Estate of Zvia Zeroni, and the European Research Council. He is the incumbent of the Philip Harris and Gerald Ronson Career Development Chair.