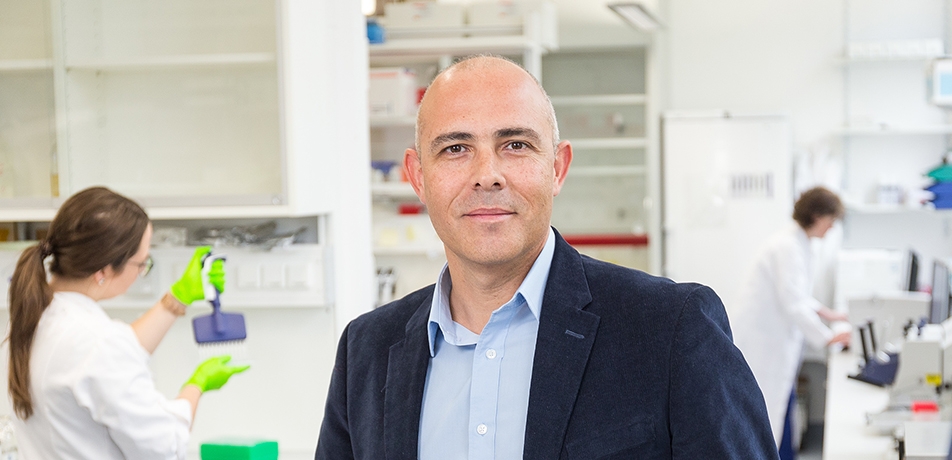

Q&A with Prof. Alon Chen

A lively conversation with the Weizmann Institute's new President

Q&A

Prof. Alon Chen entered office as President of the Weizmann Institute on December 1. A world-renowned neuroscientist with a focus on stress, he has elucidated many mechanisms by which the brain regulates the body’s response to stressful challenges, and how this response is linked to psychiatric disorders. Read his inauguration speech here.

For six years, he shuttled between Israel and Germany, where until this fall he was a Director at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry in Munich, and served as a Head of the Max Planck Society-Weizmann Institute of Science Laboratory for Experimental Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Neurogenetics. He has stepped down from that role in Germany to concentrate on his Weizmann lab and his new role as Weizmann President.

Born in Israel in 1970, Prof. Chen received his BSc and MBA from Ben-Gurion University. He earned his PhD from the Weizmann Institute, and did his postdoctoral fellowship at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, where he was a Fulbright and Rothschild Scholar. He has just completed editing a book, Stress Resilience, which is expected to serve as a seminal textbook for neurobiology students and psychiatrists. He is the first incumbent of the Vera and John Schwartz Professorial Chair in Neurobiology.

You’ve spent your scientific career focused on the neurobiology of stress. And now you’re stepping into a big job. Aren’t you a little stressed?

I think sometimes people confuse stress with excitement or focus. Stress is always a challenge to the body, but it’s not necessarily all negative. Stress challenges your emotions, cognition, and your body and at the same time it helps drive people to achieve great things. Sometimes stress simply helps us get things done. Becoming President is an honor and a challenge—one that will create ‘good stress’ and drive me to do things I want to do: be creative, and break boundaries.

In neurobiology, when we talk about stress we also talk about coping. One way I’m going to cope with the responsibility of being President is to build a team that can truly support me. In addition to the outstanding people across the Weizmann Institute, I also will have four vice presidents, who—in addition to being outstanding scientists, ‘fluent’ in the world of science—are also superb managers, and we will work together as a cohesive team. When people feel stressed, it often helps to sometimes take a step back and remind themselves what their mission and driving force is. In my case, I am passionate about ensuring science makes a difference, and I keep on going back to that wellspring of passion.

How will you balance your science and your leadership?

First, naturally, I’ll reduce the volume of my research. Together with my lab at Max Planck, I’ve been mentoring and supervising about 50 students, scientists, and technicians in more than 100 projects. In the near future all that will be reduced to about 10 people in my Weizmann lab, and we will be more selective in the projects we take on. I am now at a point with my own research interests where I’m ready to partially ‘zoom out’ and convey to broader audiences the importance of understanding the mechanisms of stress and its relevance in life.

Please give us a small window into your research.

During my PhD, I was interested in brain control of reproductive functions, and of bodily functions more broadly. Then I turned to stress research: I was intrigued by the impact of stress on human health and how it is related to pathologies like eating disorders, anxiety disorders, and depression. Stress is also a fantastic system to study how the entire brain functions, because when you are stressed, your brain activates many different systems, influencing emotions, appetite, anxiety, fear, memory, attention and locomotion.

My lab has studied stress from a variety of angles, starting with the mechanistic aspect of genes, cells, and circuits all the way to studies in humans. This scope has allowed me to appreciate basic and translational research, and how they inform one another.

On that note, the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry is the only MP institute with an affiliated hospital, in this case a psychiatry hospital. How has your work there enhanced your research?

The added value for my research has been immense. There are two kinds of scientific approaches: bottom-up, research that identifies the molecules, genes, circuits, and pathways in animal models, and then takes those findings and see if they are relevant to humans. The second approach is top-down, where we first explore a medical need or a phenomenon in human, in health or disease, and then investigate its components and mechanisms and bring them to the preclinical (animal) lab setup. It is practical and effective to do science both ways.

What can Israeli science learn from German science, and vice versa?

My lab at Max Planck is an amazing place. My German colleagues are very methodical, thorough, and the quality of their work is very high, at all levels—from technicians to principal investigators. Israeli scientists tend to dare more. They are boundary-pushers, risk-takers. And this is what enables exceptional scientific creativity. There is plenty we can learn from each other, but I must say I learned to appreciate ‘the Weizmann way’ of doing science even more. When I first set up my department in Germany, it was very quiet; I was the main person doing the talking. It took people months to call me by my first name. I’m leaving it much more Israeli than it was in terms of it being a more open atmosphere. Now everyone else is doing the talking, and I don’t have to say a word!

But there is still plenty for us to learn. I’m not a fan of Israeli hutzpah at all. I think we need to make sure to extract all that is good about hutzpah —assertiveness, an ability to question authority and accepted beliefs, push boundaries — but leave behind the aspect of flippant arrogance, or what other cultures perceive as such. I learned this myself the hard way! During the first week of my postdoc fellowship in San Diego, I listened to a presentation by a member of my new lab group. When she was done, I raised my hand and very matter-of-factly told her that she was wasting her time with the genetic approach she has taken. The room was suddenly silent, and then she burst out in tears. I was in shock and felt terrible; in my eyes, I was being direct since I was trying to help her and save time and resources. But I clearly needed to learn how to say it better. We later on became good friends so I guess it wasn’t that bad.

What are you most proud of in your work?

My students and postdocs. The fact that I was able to provide them with the freedom to explore their own ideas. I have my vision, but within this broad vision, they have the ability to go wild—and that has led to great things. Seeing them develop into fantastic scientists and explore their ideas freely makes me very proud.

What’s top on your agenda as President?

First and foremost, to continue to recruit the very best scientists, and not only Israelis. It’s all about the people. Weizmann is ranked high globally, so there’s no reason we can’t recruit the very best in the world. They don’t have to be Jewish or Israeli citizens. I am a big believer in the Weizmann policy of hiring scientists solely based on their excellence and then providing them with all they need to do top-notch research. It’s not about positions, it’s about the quality of the people and science. We’ve always done this and we will continue to do this. I don’t care if a scientist is investigating a rare green lizard in the Amazon. As long as she or he is the best Amazon green lizard scientist there is, we should recruit that person.

I want to continue to promote collaborations with leading international institutions, which will help increase our visibility. We are a well-known entity in Israel, but there’s more to do overseas: our international name recognition doesn’t match our scientific prowess. Daniel Zajfman has always said: ‘We should not just be an ivory tower; we should be a lighthouse.’ And I fully agree. To do that, and to push the boundaries of research, we also need to nurture translational and applied research, so that as many people as possible can benefit from Weizmann discoveries. So, even though we should never sway from our basic research mission, I also want to build new bridges with commercial partners.

What role does, or should, the Institute play in Israeli society?

We are extremely active in science education—we have made major contributions there, via the Davidson Institute and the Department of Science Teaching, and we should continue doing so. Our alumni have made a major impact on Israeli society, fueling this country’s economy, and are unofficial ambassadors for Weizmann and Israel everywhere they go. Of course, our biggest impact is our science, because discovery is the strongest engine for economic growth, and for improving lives.

What kind of role do you envision the ‘Weizmann family’ playing in the years to come?

In every good family, relationships become stronger throughout the years, and the family branches out and becomes more diverse. Its diversity is also its strength. This is how I perceive the future of the Weizmann family. I want it to be bigger and stronger. I want people to be even more involved and engaged. But, like any good student, I’m going to start by listening and learning. A donor who visited with me recently said it best: ‘The Weizmann Institute is Israel’s best asset.’ I love what she said, and she’s right.