Stories spring forth

A Q&A with prolific Israeli novelist Meir Shalev, recipient of an honorary PhD

Q&A

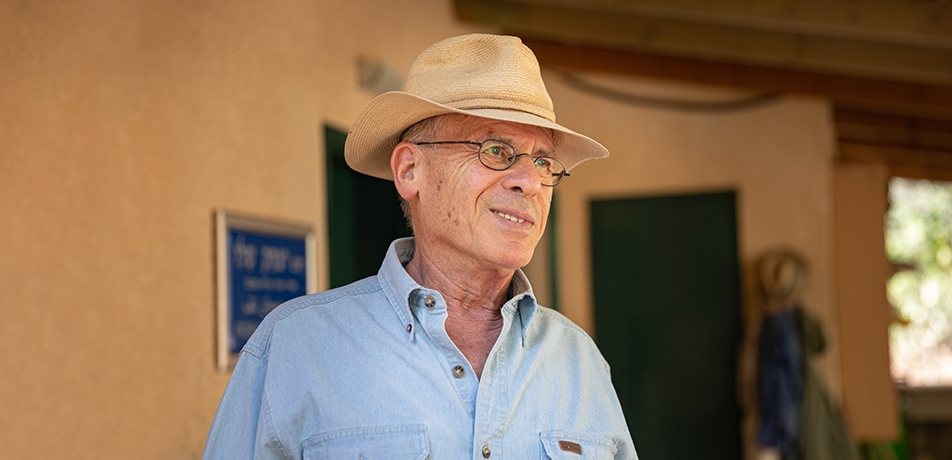

He weaves magical, intricate tales, avoids the role of preacher, and sees writing as a meticulous, painstaking form of craft. Meir Shalev, one of Israel’s most popular and critically acclaimed writers and a celebrated Israeli literary figure abroad, will receive the Weizmann Institute of Science 2020 PhD honoris causa in a ceremony on November 17. He will be the keynote speaker.

Sitting next to a stone bench outside his home, Meir Shalev carefully extracts a seed from its pod with the practiced movements of one who can measure an entire lifetime with the palm of his hand. His fingers, now carefully harvesting a plant, will later write a few more lines in his new novel and proofread his newspaper column. In the garden surrounding Shalev’s modest home in a Galilee region village, between the labors of the land and the toils of the mind, the dusty heat of late July is gently relieved by Jasmin shrubs, lemon trees and a single sea squill already in bloom.

Shalev’s novels, essays, and children’s books have been translated into many languages, and some have been adapted to plays. His opinion column, published regularly in the weekend edition of Israel’s most widely read newspaper, treats current affairs and cultural issues with sharp, sophisticated humor.

Words, says the narrator in Shalev’s second novel, Esau, can travel faster than the wind, faster than light, and even faster than the truth. To his mind, words transcend all else. What, then, is the position of the person creating the words in this hierarchy? Shalev answers simply: “We have an important cultural role: to tell stories.” This would make an excellent closing statement, but it is, in fact, where everything starts.

Q: Many people expect writers to act as prophets. Where do you stand?

Because we are eloquent, well-spoken individuals, we are automatically appointed preachers and watchmen unto the house of Israel. In my newspaper column I regularly voice my political opinions, but I am very careful never to write political books. I don’t use literature to promote political agendas, and I don’t use my politics to promote my literary works. Some accuse me of laboring under an elitist misconception, but by the same token, why aren’t Weizmann Institute’s professors held to the same expectations? They too are intelligent people with a firm grasp of current affairs, and they are obviously capable of discussing various phenomena in a logical manner.

Q: Scientists are motivated by their passion to understand how things work. What motivates you to write?

I write mainly so that I can live with myself. So that I know I’m doing something I love and appreciate, and that I can conceivably be good at. I started writing fairly late in life, publishing my first novel when I was 40. Before that, I worked in television with considerable success, but I wasn’t comfortable with what I was doing. The decision to attempt a new profession at 40, with a family and two kids, was quite bold. I considered becoming a teacher, like both of my parents, but I was honest enough with myself to admit that I lack the necessary patience. My other option was zoology, but I was already too old. Because I’m a voracious reader, because I like hearing stories, love language, and can string words together with some skill, I decided to give writing a try.

Q: While you are writing, do you experience moments of inspiration?

“Sometimes, on very rare and happy occasions, an idea comes to me while I’m writing that I didn’t think of in advance, seemingly of its own. For example, in Esau, I describe how the narrator and his twin brother have an appointment with an optometrist, who gives both of them the same eyeglass prescription. Their father, a renowned miser who is also short of money, buys them a single pair of glasses. The fact that they have to share the glasses shapes their lives. I didn’t plan that in advance, it just flowed through my fingertips onto the keyboard and when it did, I had to stand up and walk around the room for a little while until I calmed down. I suddenly realized what a treasure fell into my lap, as if it was launched from somewhere outside the book to land in the middle of it. But this is a very rare occurrence.”

Q: The act of writing moves between the polar opposites of revealing and concealing. The writer knows how the story ends, but leads the reader step by step all the way to the finish line. How do you accomplish this?

I only start writing when I have a general outline of the plot. While I’m writing, I can take a character out, add a protagonist, or create a dramatic turn of events. But the overall framework of who marries whom, who is born to which parents, and who dies and when and why, these are all elements I know for certain from the outset. A novel is a work of philharmonic complexity, and novels of the type I have been writing, with multiple protagonists, spanning many years and several generations, must be conducted with careful attention and a firm hand.

If there’s a surprising event in the plot, I’m careful not to give it away too soon. For example, in my first novel, The Blue Mountain, the reader does not discover that one of the protagonists is actually a mule until about page 200. Until that point, he is described only as a hard worker with big ears. When this fact is revealed, it’s a definite surprise. Readers told me they read back to see whether there were any clues leading up to this discovery.

Q: What techniques do you use to keep track of these complexities?

Amos Oz once told me that readers should never be allowed to know what I’m about to tell you, because they must be made to believe that there is something mysterious about what writers do. I argue that even when the minute technicalities of writing are revealed, there remains something mysterious about them that even I don’t fully understand and that still surprises me.

I keep a little notebook with diagrams, research material ideas. I draw a chart with the characters’ names on one axis and the years on the other, and I fill in what happens to each character in each year, so I don’t end up with someone living in Germany at the same time that he is reported to have died in Tel Aviv.

Also, because my narratives do not progress in chronological order and are delivered through first-person narration, which means that the narrator jumps from one thing to another the way people do when they tell a story, associatively, I use sticky notes to help me keep track of things. Here, for example, the note reads ‘the pregnant math teacher.’ This refers to a computer file that describes what my narrator had to do with the pregnant math teacher; a conversation, a request she made to him. And this note reads ‘asks him to stay.’ I know exactly what this means. For each book I create dozens, sometimes hundreds, of notes like these.

Q: How do you weave these notes into a story?

When I start writing, I write different scenes in the characters’ lives. Each scene is in a separate file. The story is not told in chronological order, and my narrator is not a particularly organized person, but the way in which he reveals the information should be interesting and must make sense. So my floor is littered with sticky notes, and for about two or three weeks I walk around holding a long, supple stick, using it to move the notes around. If there were any onlookers, they’d probably find this practice extremely silly. After I finish arranging the notes, I sort the computer files in the corresponding order and then read the whole thing and realize that while it might look great on my floor, it is horrendous in book form. And then I go back to the notes. This process repeats itself four or five times. I find the physical act of standing over the notes and moving them around to be oddly inspiring in and of itself somehow.

“When I edit the printed out texts, I use a classic Parker 51 fountain pen that belonged to my father, poet Yitzhak Shalev. He has written many poems using this pen.

Q: When you are writing, do you think about your readers?

No. When I’m writing, I ask myself would I be interested in reading this. I have considerably more experience as a reader than as a writer, and greater success, and I’m honest enough with myself to be able to say: this is garbage, this is pretentious, and this is just plain boring. I think that’s a good quality in a writer.

Q: What are you reading these days?

Right now I’m hardly reading anything. I’m writing. During this stage I read very little, because it tends to get in the way of my work. If I do read, I read little and only books I’m very familiar with and that are pleasantly inspiring. I also read old topographical maps. I have maps dating from the British Mandate. A topographic map is a book that requires you to translate two-dimensional into three-dimensional information. You read the terrain, mountains, hills, ravines.”

Q: You books are rooted in the landscapes of your childhood. What do you think gives them a universal appeal?

The local is also the universal. When I read Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd or Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls, they transport me to distant lands, back 150 or 250 years, but I feel completely at home, the same way I do when I’m reading love stories in the book of Genesis. The human soul changes little across time and space. Cultural differences obviously exist, but love, jealousy, death and sibling relationships are shared by many cultures throughout many periods.

A Druze man once told me that my novel The Blue Mountain was written about his home town of Daliyat al-Karmel, because the old farmers there are exactly the same as the farmers in my book. So although I wrote about a socialist Zionist village with strict regulations and the labor movement and the religion of labor and Hebrew, there is something about old farmers living on their land that seems to be the same everywhere. When my children’s book My Father Always Embarrasses Me was translated into Japanese, one critic wondered how a Western writer can have such profound understanding of the psychological complexities of the Japanese family. In the end, people are very much the same wherever they are.