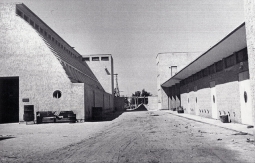

The Weizmann Institute of Science preserves the historic structures and compounds while addressing ongoing needs related to the development and progress of science, fully understanding the importance of conservation and its significance to the Institute's visitors, graduates and the State of Israel's built heritage.

Each of the historic buildings marked for preservation is involved in Israel's scientific development – from Dr. Chaim Weizmann's laboratory in Daniel Sieff Research Institute and the invention of the acetone; through the development of WEIZAC, Israel's first computer in the Jacob Ziskind Building; the Koffler Accelerator and the Weissman Building of Physical Sciences, in which atomic energy was studied; and others.

In addition to the historic buildings, the campus encompasses several historic landscape sites that encapsulate the Institute, and represent its landscape heritage.

There are 24 buildings / sites for preservation at the Institute. The Construction and Engineering Division is required to renovate and refurbish buildings and sites designated for preservation from time to time. Such work is carried out according to strict standards, with sensitivity and historic responsibility.