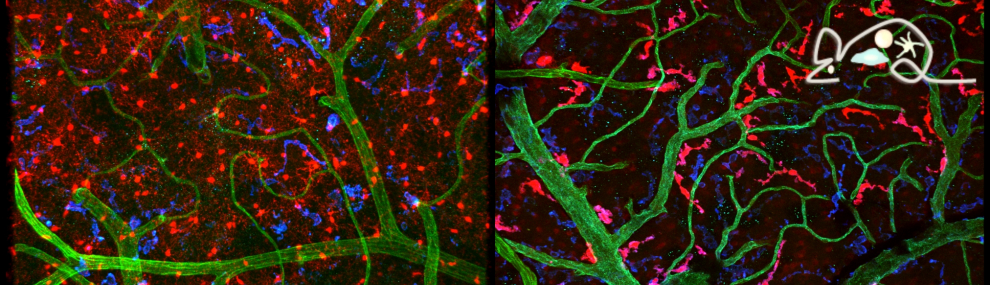

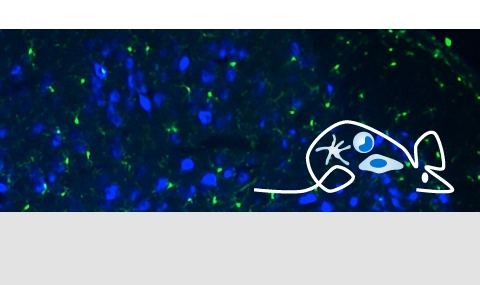

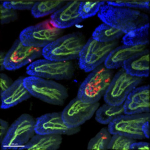

Tissue resident macrophages in brain, gut and the lung - brain / lung / intestine / fat tissue

Tissue macrophages are strategically positioned throughout the organism. As professional phagocytes, they ingest and degrade debris and foreign material, including pathogens, and orchestrate inflammatory processes. Macrophages can be generated from three distinct sources: two early, currently considered transient, hematogenic waves initiated in the yolk sac that seed tissues prenatally, and a pathway involving hematopoietic stem cells and mature blood monocytes, that persists throughout adult life. Most macrophage compartments are established prenatally, and develop independently from each other in their respective host tissue. These cells locally acquire distinct epigenomic and transcriptomic identities, through the imprint influence of the respective microenvironment. While recent studies have revealed critical contributions of tissue macrophages to organ development and homeostasis, specific involvement of discrete subpopulations in the maintenance of the healthy balanced steady-state remain however to be elucidated. Using the mouse as a model, we aim to define functional contributions of specific tissue macrophages to physiology and pathophysiology.